Remake: Le Madison

A/NL 2008/11, PAL 16:9, 50 min, colour, stereo

3 channel projection

© Exhibition view: I can't stand the quiet!, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck, 2011. Photo: WEST.Fotostudio

The video installation Remake: Le Madison presents the live recording of the performance Le Madison on July 1st, 2009 at Kunstraum W139 in Amsterdam. For this intervention, participants responded to a call in newspapers and on the internet to perform a group dance at the art institution W139. The dancing steps could be rehearsed with YouTube Lectures (Le Madison Lessons 1 - 3) ahead of the performance. The collaborative dance project was recorded by multiple cameras and will be screened in Remake: Le Madison in a 3-channel-projection. (school)

© Video stills Remake: Le Madison

© Ausstellungsansicht: Tanz Es!, Ursula Blickle Stiftung, D-Kraichtal

Le Madison

Art intervention on July 1st 2009, W139, Amsterdam

The Madison is the name of a line dance that came to Europe from the USA at the beginning of the 1960s, spread chiefly via film. The dance consists of a predetermined combination of steps by dancers who move without touching each other while standing alongside one another in a line—coolness gone Swing, so to speak.

Annja Krautgasser’s adaptation of the Madison theme is an allusion to a famous scene in the 1964 film Bande à part (Band of Outsiders) by Jean-Luc Godard, and so also to the medium responsible for the dance’s popularity in Europe in the early 1960s. In the scene concerned, one of the key scenes of the film, the three main characters Odile, Franz, and Arthur break into the Madison in a Paris bistro as if they were the only people there.

© Documentation of the art intervention Le Madison, W139, Amsterdam.

Photo: Simon Wald-Lasowski

The isolation as a group within the social corpus that they also experience as outsiders is expressed in the particular form of the Madison: as a line dance it is carried out by several participants at the same time, although each person involved does so in isolation and not with a partner as a direct counterpart.

The venue for Annja Krautgasser’s remake of the scene is an Amsterdam art space that provides the institutional framework of a white cube characterised by the then current intervention The Cartesian Grid by the artist Bernd Trasberger. In this work, the neutrality of the art space is exaggerated by a rational white grid while also being broken to the extent that Trasberger also introduced items from older art projects to allude to social utopianism. So Krautgasser’s intervention also contains utopian potential when the venue for her project is a context that is both abstract and occupied by concrete utopian ideas. Le Madison was performed with a live band and with about forty dancers who had answered an online call for participants and studied the steps in advance. In contrast to the original film scene, it was the collective experience and shared knowledge about and in the dance that were in the foreground. In performing the re-enactment, there is a shift in the approach as it opens up towards a larger social context, so suggesting the symbolic opening up of an art space—i.e. to a form of institutional critique.

© Video still Bande à part (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964)

It is less of a direct political message of the kind seen in Adrian Piper’s Funk Lessons, 1982, where the artist showed a white audience how to dance to Afro-American funk music to redirect racist prejudice into cultural understanding. The intention shifts in Krautgasser’s piece more onto a level of (self-) reflection to the extent that here the authorship and the role of the artist are posited by an implicit adoption of distance.

(Patricia Grzonka)

VIDEO

: Remake: Le MadisonA/NL 2008/11, PAL 16:9, 50 min, colour, stereo

3 channel projection

Happening on July 1st 2009 @ W139, Amsterdam

www.le-madison.net

Performers

: Luc van Esch, Tashi Iwaoka, Sarah van LamsweerdeCameras/Dancing lessons

: Krzysztof Wegiel, Julias WillmsCameras/Shooting

: Alex Ivanov, Assen Ivanov, Svebor Kranjc, Krzysztof Wegiel, Julias WillmsLight setting

: Paul SchimmelAudio recording

: Alvin van VeenAudio mastering

: Martin SiewertLive music

: Westhell5, www.westhell.nlExhibition setting

: Exhibition Belvedere @ W139 by Bernd TrasbergerThanks to

: Miriam Bajtala, Andrea Bozic, Gijs Frieling, Wolfgang Oblasser, Rudi Palme, Sabien Schütte, Marleen van der Weerd, Julia Willms, Annette WolfsbergerSpecial thanks to all participants!

Supported by

:Stichting

agentur:

www.agentur.nl

newdancestudios

www.newdancestudios.com

W139

, Warmoesstraat 139, 1012JB Amsterdamwww.w139.nl

Give me a body

by Eva Maria Stadler

© Exhibition view: Le Madison Lessons 1 - 3, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck, 2011. Photo: WEST.Fotostudio

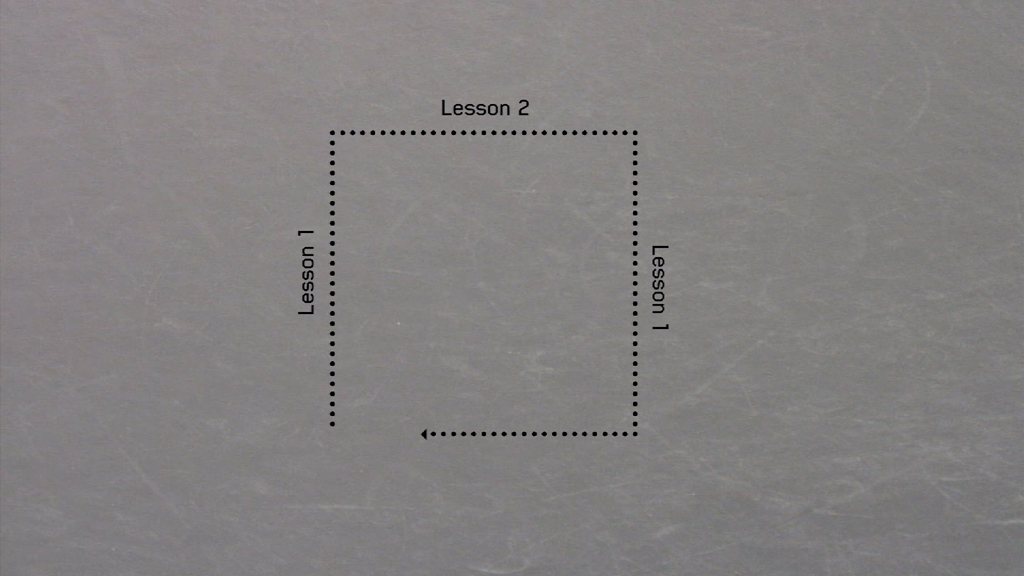

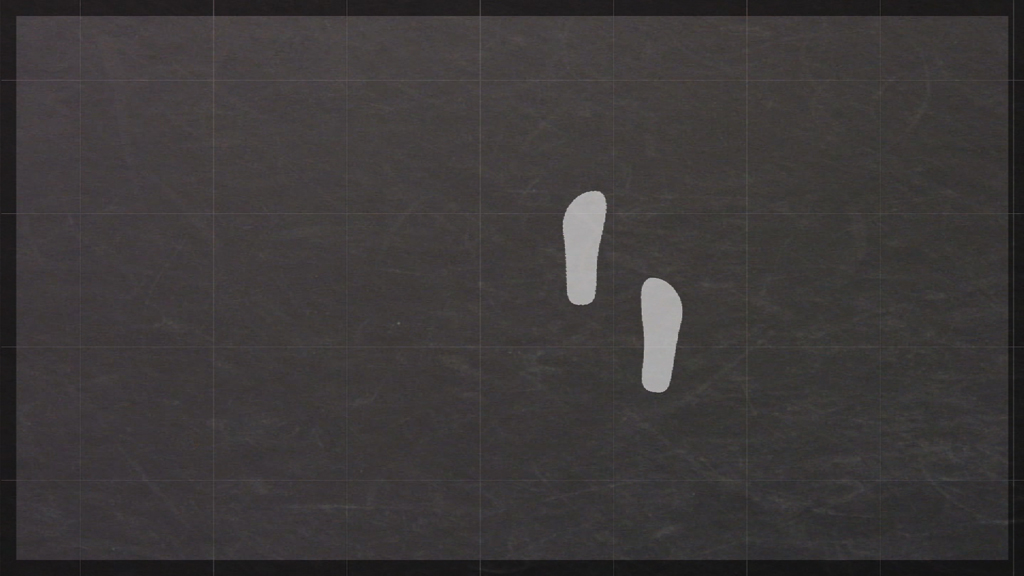

(...) Annja Krautgasser took this dance scene as the departure point for her film and her interventionist performance, Le Madison, that was realized in 2009 in Amsterdam and which she now takes as the basis of her exhibition I can’t stand the quiet! at the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum. At the Amsterdam Kunstraum W139, Annja Krautgasser works with the spatial intervention of artist Bernd Trasberger, who in The Cartesian Grid covers the entire space with a line grid. For her premiere, Le Madison, which the artist had called out via Internet invitation, was staged with 40 men and women dancers who responded to the invitation. The participants had the opportunity to study and try out the dance in preparation for the event, using the Internet course Le Madison Lessons 1–3.

A space that recalled the “Domestic Landscapes” of the Italian group Superstudio, which in the 1960s was concerned with city utopias and industrial architecture, served as a stage not only for the dancers, but also for a live band, who provided musical accompaniment for Le Madison. What was missing was the audience. Only several camera operators and the artist herself comprised the viewers.

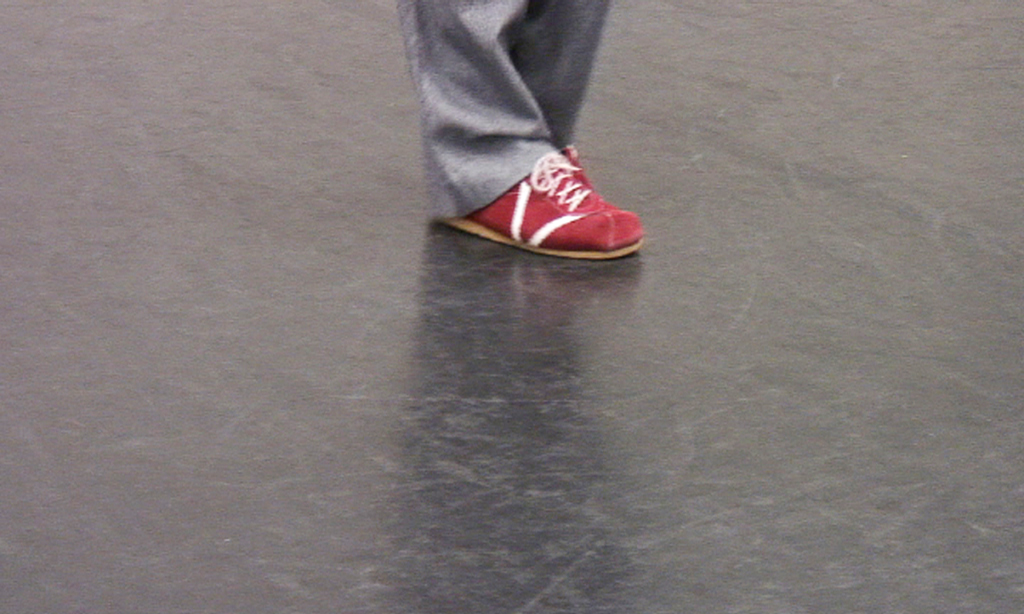

The set: an exhibition space, room graphics, the dancers, the artist, camera people; they are all elements of the choreography.

“Give me a body,” exclaims Gilles Deleuze in the eighth chapter of his study of cinema, The Time Image, and addresses a paradigm change according to which thought would no longer be separated from the body, the body would no longer be an “obstacle”; rather, thought would be located in the “categories of life,” by which Deleuze means behaviors such as sleep, grogginess, or tension. The matter is to understand why a non-thinking body is capable of being a body that is no longer an intermediary, but rather a thinking body, even when it is not thinking. “Give me a body” means first of all pointing a camera at an everyday body, says Deleuze, for it is through the thinking body that cinema is able to couple with thought.1

© Video stills Remake Le Madison

The camera as an instrument has been drawn on for the study of the body, its behaviors, and its positions, in order to, on the one hand, allow it to measure; on the other hand to speak, to think. To give a body would also mean introducing it into a ceremony. Deleuze speaks of the potential that film has of allowing a body to be created in a ceremony, in the liturgy, to “make” it. Film would be able to create it, to bring it out, yet also to let it disappear.

In Annja Krautgasser’s performance, ceremony, the “thinking” body, and the language of film form a constellation that now becomes the connecting point of her exhibition.

Since the beginning, the Madison has been tied to the media. Lessons, in which the steps were demonstrated, were shown on television. First of all, therefore, the individual practice stands in the foreground, before the collective performance can take place. The dance is not practiced together, and its ceremony consists instead of its individuation, which is accentuated by the grid applied to the room. The relationship of the dancers to each other is determined spatially and not motivated by the contents of the dance.

Having come from a background in architecture, Annja Krautgasser is interested in construction by means of spatial and medial coordinates. In her earlier films and installations, her concern was often the expansion of spatial and geographic concepts, such as, for example, in the network-based media installations IP-III, which presented the tracks that Internet users leave behind with their IP addresses as interactive room sonographics. While one concern was to question modern cubings and to explore a new grammar of room structures, another concern was the behaviors of Internet users, their participation and activation, which for Annja Krautgasser was an essential reason for reacting to or encouraging a changed relationship between actor and recipient.

© Video stills Le Madison Lessons 1 - 3

The dancers, men and women, who decided on participation in Le Madison and in the current I can’t stand the quiet! are protagonists of a group dance and audience for an artistic intervention, as well as users of a media network. The complex interplay of the various role designations requires a specific practice for performance that closely approximates Gilles Deleuze’s thinking bodies. Thus Jean-Luc Godard, in order to explain the behaviors of the bodies in terms of “categories of thought,” allows the figures in the dance scene in Band of Outsiders to dance for themselves.

The concentration on one’s own movement, on immersion in one’s own body, has been decisive for Annja Krautgasser as a motivation in the literal sense of the word, a motivation that creates a theater for itself. The camera is given the task of documenting the events. Moreover, Annja Krautgasser installs a camera behind the camera; she thus captures on film and in photographs not only the dance but also her own artistic work as director, choreograph, and artist, at the same time being involved, as the dancers are, less in a performance than in a practice.

© Video stills Le Madison Lessons 1 - 3

The relationship between dance and space, with which Annja Krautgasser works, does not primarily emerge first in the twentieth century, when the tendency toward automation of the body was considered as a means of liberation from space. In the social dances such as the courtly Minuet or the upper class Waltz, not only politically motivated structures can be recognized, but also cultural influences and a specific understanding of the body relative to the dance.

For Siegfried Kracauer, dance at the beginning of the twentieth century had been reduced to a scansion of the age. Concern is with the presentation of the rhythm in itself, the cult of movement and not the movement as cult, he writes in his essay “Travel and Dance.”2 Kracauer is occupied with the formalized movement, whose mechanics and ornamental formations he describes especially in the formations of the American Tiller Girls. His focus in this is on a mathematical demonstration and not the movements of the individual girls, states Kracauer and he relates this observation to processes of the economy and production, whose expression he sees as the “mass ornament.” The individual has no concept of the whole; ornament is not included in their thinking. There is no line that leads from the elements of the mass to the whole figure, he claims. Some time later, Heiner Müller would describe the coupling of the organic and the mechanical in the historic avantgarde as a marriage of man and machine. The continuing discourse of this connection in the age of new technologies “comprehensively takes hold of the human body, which, interconnected with informational systems, has even produced new phantasms in postdramatic theater,“ concludes Hans-Thies Lehmann in response to Müller.3 Similar to Kracauer, Lehmann sees as a consequence of mediatization, a tendency toward disembodiment, a totally superficial sexualization, which separates the body from desire and from Eros.

Thus Godard, in his dance scene in Band of Outsiders counteracts the separation of desire and Eros, in that he locates the production of affect in the area of the imagination. More than physical closeness, as it is lived out in the Waltz or classical Latin American dance, the concern is with the gauging of space or with localization the self.

In the same year that the Madison achieved fame through the television show, Elias Canetti’s Masse und Macht (Crowds and Power) was published. Based on mass events that had strong personal significance, such as Hitler’s march into Vienna, Canetti’s comprehensive study traces a diversity of crowd phenomena and power structures, located between the fear of others and the dissolution into the mass. The crowd is a formation shaped by affect, writes Canetti. It occurs at the moment of release in which all who belong to it lose their individuality and feel the same.4

In overcoming the fear of closeness, which results in the readiness to merge with the crowd and to lose individuality, Canetti sees an act of relief, because the individual no longer stands alone in the world.

© Video stills Le Madison Lessons 1 - 3

Le Madison can be seen here as an example of group-dynamic behavior that stands in connection with the emergence of television and its increasing popularity. The individual takes refuge in the collective. The set-up of the stage provides the space that allows for locating oneself in the crowd, for being at the same time similar and different.

Annja Krautgasser works with the pairing of social implications in media and with this transfer brings out the demarcations along which something like a media reality is depicted. (...)

1 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, London, 2005, p. 151.

2 in: Siegfried Kracauer, translated by Thomas Levin, The Mass Ornament, Cambridge, MA 1995,

p. 65f.

3 Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatisches Theater, Frankfurt/Main 1999, p. 363.

4 Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power9, New York, 1960, p. 16.